Sparking Debate to Grow Critical Thinking

February 4th, 2026

One of the greatest boons for history educators in the last decade has been the popularity of the musical Hamilton. Suddenly, the Early Republic of the US is no longer the exclusive purview of stuffy academics, but cool (insofar as musical theater can be considered cool). What makes the story of Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and the Founding Fathers so ripe for drama is the obvious enmity between the real-life figures that the characters are based on. As we read about the men and women of the past, we can’t help but recognize the same penchant for partisan politics, personal slander, and uncivil discourse that can pervade the headlines of our present day. But just as often, we observe the tendency of our forebearers to compromise, to work together, and to disagree with conviction and respect. As Jefferson would say upon his inauguration to the presidency, “[E]very difference of opinion is not a difference of principle.” While we learn about the disagreements of the past in the classroom, it’s just as important that we as educators foster and cultivate an environment that provides students with a model of civil disagreement.

One of the greatest boons for history educators in the last decade has been the popularity of the musical Hamilton. Suddenly, the Early Republic of the US is no longer the exclusive purview of stuffy academics, but cool (insofar as musical theater can be considered cool). What makes the story of Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and the Founding Fathers so ripe for drama is the obvious enmity between the real-life figures that the characters are based on. As we read about the men and women of the past, we can’t help but recognize the same penchant for partisan politics, personal slander, and uncivil discourse that can pervade the headlines of our present day. But just as often, we observe the tendency of our forebearers to compromise, to work together, and to disagree with conviction and respect. As Jefferson would say upon his inauguration to the presidency, “[E]very difference of opinion is not a difference of principle.” While we learn about the disagreements of the past in the classroom, it’s just as important that we as educators foster and cultivate an environment that provides students with a model of civil disagreement.

Students today inundate themselves with views of the world that are intentionally combative, and to counter this we provide alternative approaches to problem solving. The emergence of social media algorithms and 24-hour news cycles begets the need to capture a most precious commodity: our attention. Conflict generates more views, and as a result it drives much of the casual connection to the outside world. Without providing an example of how things can be different, students won’t have a constructive model that they can carry forward into their adult lives. In the classroom, I provide students a positive view of disagreement based on shared problem solving, rather than competition.

Before students begin their first debate in the classroom, I like to solicit what they think would be some winning tactics. Some suggest dismissive invective, personal attacks, or general volume. Some even propose blackmail. But as their enthusiasm wanes for the game of entertaining these morally dubious maneuvers, they grow more reserved. They want to set ground rules. They want each other to be respectful, to listen, and to be supportive. They recognize that good arguments don’t mean bashing the other side; it means carefully considering the perspective of the person across the table from you. We spend a lot of time in class reading, writing, discussing, and evaluating arguments. We do this because not only does it give us an insight into the thoughts of the past and present, but it also provides students with a framework to help understand how people approach problems, and how to better connect with different viewpoints. Growing this empathy to really consider the world through the eyes of another helps train the muscle of civil discourse. In class, students will be forced to support arguments or positions they don’t believe. They begin talking not about the other person, but rather considering what they’re saying and whether it is actually beneficial. Developing this skill to argue requires the development of the skill of empathy. To put oneself in another’s shoes. And that gives students the experience of disagreeing with civility. Civility has come to be a byword for politeness in our culture, but it really conveys approaching something with a mind to the collective good. Beyond wanting to advance our personal needs, for a republic to prosper, its citizens must think outside of themselves. Students get the opportunity to practice this empathy and civility by passionately arguing their perspective, while respecting others participation in the same community. They then take these skills and use them to explore more of the planet that we all share.

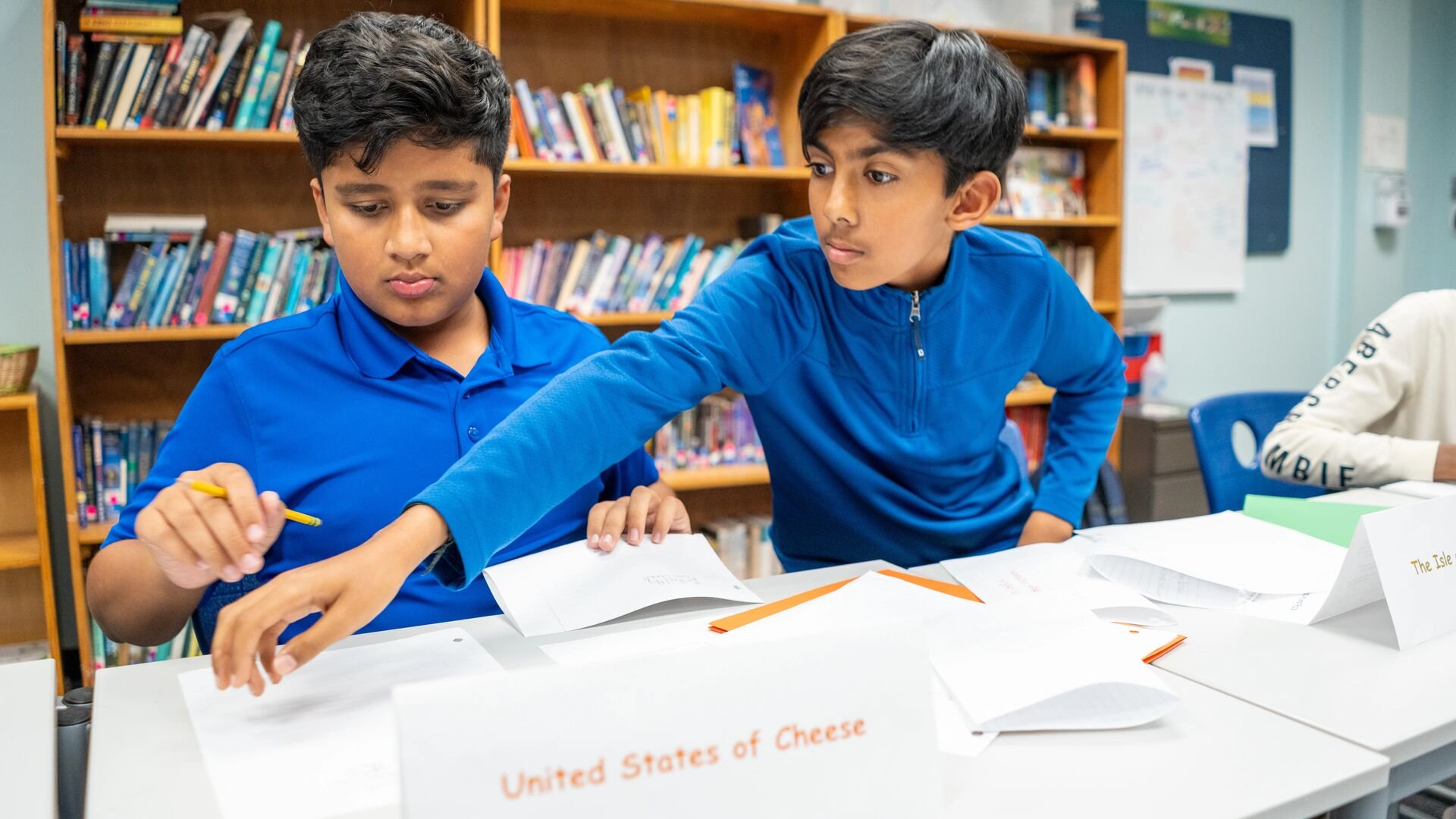

Outside the classroom, I have the great fortune to sponsor our middle school Model United Nations. In addition to students researching world politics and learning about international relations, we have the opportunity to participate in interschool conferences. Students will often ask how they win awards at these conferences, and they are invariably shocked to learn that the “game” is about collaboration, coalition building, and compromise. Who can most effectively marshal support and convince others to work together. Who can break down barriers through conversation and argument. We help students prepare for conferences by conducting research into other cultures, other positions on the global stage, and learning how to work together to develop policy recommendations that take into account those across the table from them.

In history class and at Model UN conferences, students see over and over that disagreement doesn’t necessitate hatred. Instead, we seek to confront the problems in front of us together to argue for a better future for all. At Charlotte Prep, we seek to provide students with the skills and experiences necessary for them to not only be informed, but to appeal to their better natures and stride forth into the future with the knowledge that they can stand by their principles while remaining respectful and open to the world around them.

More News from Charlotte Prep

Feb19Second Graders Host an Outside-the-Box Lesson in Black History

Feb19Second Graders Host an Outside-the-Box Lesson in Black HistoryOur second graders recently served lunch to Charlotte community members along with sides of information about the lives of more than 40 remarkable African Americans for Black History Month.

See Details Feb12Brandon's Prep Story

Feb12Brandon's Prep StoryMy name is Brandon, and I’m an eighth-grade lifer here at Charlotte Prep. I’ve been a student here for ten years, which makes Charlotte Prep not only a place where I've learned but also where I’ve grown up. What I’ve experienced is a school that intentionally helps us become confident learners, strong individuals, and caring members of a community.

See Details Jan29Anchor Tasks Ground New Learning

Jan29Anchor Tasks Ground New LearningAnchor tasks help students tap into their prior knowledge to prepare them to engage in learning something new. These brief discussions or activities make meaningful real-world connections to the concepts and skills students are about to explore.

See Details Jan21Prep to McCallie—and Beyond

Jan21Prep to McCallie—and BeyondHigh school placement at Charlotte Prep combines personalized guidance, a strong reputation, and deep relationships with both local high schools and prestigious boarding schools across the country. Read what these alumni say prepared them for success.

See Details